The Oxford English Dictionary defines the word “literal” as “taking words in their usual or most basic sense.” Simple enough. So should the Bible be read literally? The answer to that question is more subtle than it seems but can be boiled down to three words: yes and no.

“Literal” is a tricky word when it comes to the Bible. When people throw the L-word in, they are sometimes trying to talk about taking the Bible seriously or whether it is inerrant or the authoritative word of God or if it happened in real history. The word “literal” can be a stand-in for those other words and can act as a tribal marker or ID badge that can be waived around for identification purposes. “Do you believe the Bible is true?” “Yes, I take it literally. Every word.”

But when we looked more closely, taking every word of the Bible absolutely literally doesn’t do right by what the Bible is actually saying.

What I Am Not Saying

It might be good to clarify what I am saying and what I am not saying.

I believe the Bible is the authoritative word of God, written and compiled across centuries by God and by human individuals and groups in disparate times, cultures, and places.

It is also historical, at least the parts of it that are written as history. As Francis Schaeffer said, “If you were to rub your hand down the side of the cross, you would get a splinter.” Right there with you, Fran.

I also think that the Bible is without error, at least in the original autographs. There are plenty of examples of translators distorting the original texts either intentionally or accidentally. However, because of manuscript discoveries in the last century, scholars know what the original text said in 99.9% of the Bible, bypassing any historical variants that snuck in due to translation errors. (Here is a lecture that goes into more detail on all that.)

But do I think the Bible should always be read literally? No.

The Problem With “Literal”

The problem with taking everything in the Bible literally is that it isn’t all meant to be taken that way.

The Bible is a book of books and the individual books that comprise the one, greater Book belong to different genres, are written in different styles, employ different literary techniques, achieve different aims, and often belong to different centuries. Each genre has its own rules, each section of the Bible has its own rhythms, and each book has its own ways it needs to be read. But to the man with a hammer, everything looks like a nail, and if the only tool in your literary toolbox is labeled “literal,” you are going to smash all that other stuff to bits.

So to begin to answer the question, “Should we read the Bible literally?” I would start with another question: “Which part of the Bible?”

Let’s start with genre. The Bible has at least eight major genres: law, history, wisdom, poetry, gospel, epistles, prophecy, and apocalyptic. And several of these break down into further categories when applied to the various books of the Bible. Some books even contain multiple genres inside themselves.

Some genres should be read more literally than others. As historical biography and eyewitness accounts, the Gospels have many passages that should be read literally, but even the historical aspects are full of symbol-laden language, literary devices, and organization that is the result of internal structure. For instance, did the cleansing of the temple happen at the beginning of Jesus’ ministry (as in John’s gospel) or at the end of his ministry (as in Matthew’s gospel)? Is that even the right question to ask about that event? Should we rather be asking why John and Matthew put their accounts of the cleansing of the temple where they did according to the other unfolding themes of their gospels?

Or take the example of the book of Proverbs. Reading it takes a bit of sophistication. It is an inspired book, like all of the Bible, but that doesn’t mean that if you do what a proverb says, the result the proverb predicts will happen to you. They are wisdom sayings that are generally true. This is especially the case when you have two proverbs next to each other that say opposite things. How do you take that literally? I know a man who nearly broke his faith because he kept doing what the proverbs said but not getting the promised result. Was God lying to him? Was the Bible a farce? Or was he bringing expectations to the book that didn’t fit what the book of Proverbs is?

Apocalyptic literature, like Revelation and parts of the book of Daniel, turn into mushy nonsense when you try to read them literally because they are usually a kaleidoscopic mashup of images from elsewhere in the Bible. Instead of trying to figure out if, say, the locusts in Revelation literally correspond to modern attack helicopters. You should instead build up your understanding of the image of locusts in the Bible and then bring that understanding back into the context of Revelation to begin to wonder what it is communicating.

What about figurative language? God is like a rock, but he isn’t really a rock. Death isn’t really a pit. Jesus isn’t a hen. (Luke 13:34-35) Israel is not really a she-camel, even though Jeremiah says so. (Jeremiah 2:23) You get the picture(s). The point isn’t to take everything literally but to understand what is actually being said in the way it is being said.

The Curious Case of the Golden Cube

Let’s close with a final example. In the penultimate chapter of the Bible, we step into a scene in which John is getting a tour of the New Jerusalem, which he sees descending “out of heaven from God.” The angel takes John on a whistlestop tour of the New Jerusalem and we readers are given a few important details.

The “city” is also a bride, is also the new heavens, is also a new earth (but lacks a sea). The angel has a measuring rod and reveals that the city is a square as high as it is wide. So it’s a cube. The angel says that the sides all measure 12,000 stadia. Oh, and the whole thing is made of pure gold.

The question rises: What the heck is going on?

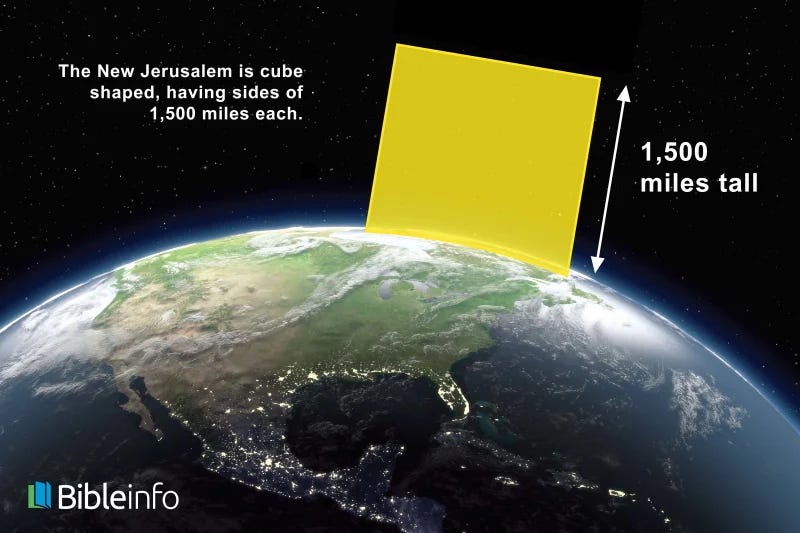

Should we read this description of the golden sky cube literally? Is this a prophetic sneak-peek at a future in which a Borg-like cube-city comes down from space and docks with Earth? If so, we’re in for trouble.

A quick Google search reveals that 12,000 stadia is roughly 1,400 miles. For context, that is just shy of the diameter of the moon (or 14 Death Stars). But that’s no moon, friends. It is made of solid gold. That is so heavy that it would completely alter the Earth’s rotation (not to mention smushing whatever poor continent happened to be under the landing site). Global catastrophe would ensue. Just as the (actual) moon pulls the world’s oceans toward its gravity, the gravity of this thing would have an even more dramatic effect, gathering the oceans around its base like a watery skirt-cone. That’d be bad news for everybody who isn’t a fish. Maybe that’s why the new creation doesn’t have a sea? Hmm.

So what DOES it mean?

If a literal reading of the Great Golden Sky Cube leads quickly leads us to redefine the laws of physics in order to imagine surviving its arrival, is there another way to understand what is going on here?

The answer is yes and it is the same process for understanding any of the images in Revelation (or, for that matter, the Bible).

Start with the assumption that the meaning of the image is grounded not only in the immediate context of the passage but also in the larger context of the canon of the whole Bible. Assume that its meaning was not some secret code to be revealed only during the End Times but has meaning that transcends time that was meant to nourish the people of God of any time.

Then begin to ask yourself questions about where you have seen images like these before? What role has the sea played in the cosmic geography of the Hebrew imagination? What does it mean for something to ascend in the Bible? To descend? Who gets married and how do those marriages go? What is the meaning of precious gems and metals? Have we seen any cubes in the Bible before?

Let’s chase that last question down and see where it leads.

There are only three cubes in the Bible: the inmost room of the tabernacle, the holy of holies in the temple, and this strange “new Jerusalem” in Revelation. If we apply the rule: “If it is repeated, it is related,” then we can assume that the meaning of the inner room of the tabernacle and the temple is related to whatever this giant golden cube means.

In Old Testament times, the holy of holies was a highly regulated place. It wasn’t a place just anybody could go in. In the temple era, it was understood to be the main “hot spot” of God’s presence on Earth, his throne room from which he ruled his kingdom. It was so holy that to enter that room was to risk death. In fact, only the high priest could enter and that only once a year during the Day of Atonement.

But the story the Bible is telling isn’t one of all of God’s holiness being “gated content” hoarded up in this little room forever. Rather, God’s goodness was always rushing out of his holy places and the result when it did wasn’t death but life. You can think of the vision in Ezekiel 47 when another prophet is getting an angelic tour of Jerusalem (remember, repeated is related) and sees a river rushing out of the threshold of the temple and anywhere the river goes, everything lives.

The story of the cube-shaped room at the heart of the temple takes a dramatic turn during the events of Jesus’ crucifixion when the curtain that separated it from the rest of the temple (and the world) was supernaturally torn in half. The meaning is clear—because of the events of Jesus’ life and death, the barrier was gone. God’s mission to totally permeate the Earth with his presence had reached a new stage.

So we return to the cube in Revelation.

Could this giant sky cube be symbolizing the ultimate fulfillment of that mission? Perhaps we shouldn’t be looking up for a moon-like object in real space, but rather be looking forward to a time when, in a sense, everything is the holy of holies, a time when what was true of that closed-off room becomes true of the whole universe.

Could the Book of Revelation be using a literary device (imagery charged with context) to pack more dense layers of meaning into its sentences than bare prose could afford?

Reading the Bible literally is just another tool in the Bible Toolbox, and the point of tools isn’t to arrange them hierarchically but to use the right one for the job it was made for. Similarly, to be a serious student of God’s meanings in the Bible will require us to allow the Bible’s own literary richness to teach us how it is meant to be read. When that happens—whether literally, symbolically, figuratively, historically, pastorally, or whatever—the result will be life and flourishing,

Photo by Guillaume de Germain on Unsplash

Excellent. I have thought about just how bing the new Jerusalem is a lot, but I have never visualized it. Super helpful.