In the Bible, Repeated Is Related

In Hebrew literature, repetition was more of a “load-bearing” literary device than it is in modern English. It is everywhere in the Bible; we just aren't equipped to see it.

The Bible is a network of internal connections and repetitions. When you find one, it is good to start exploring the connection with the assumption that “repeated is related.”

What the Bible Does With Repetition

In Hebrew literature, repetition was more of a “load-bearing” literary device than in modern English. Lacking punctuation, the writers of the Bible could emphasize ideas by repeating them.

“More than watchmen wait for the morning, more than watchmen wait for the morning.” Psalm 130:6

They could put the same idea twice in a slightly different way, underscoring their meaning:

“The cords of death entangled me; the torrents of destruction overwhelmed me. The cords of the grave coiled around me; the snares of death confronted me.” Psalm 18:4-5

They could also take the first line and invert it, making the second line say the opposite:

“Enter through the narrow gate. For wide is the gate and broad is the road that leads to destruction, and many enter through it. But small is the gate and narrow the road that leads to life, and only a few find it.” (Matthew 7:14)

They could make the second line fill in extra detail, intensifying or zooming in on what the first line said:

“But he was pierced for our transgressions, he was crushed for our iniquities; the punishment that brought us peace was on him, and by his wounds we are healed.” Isaiah 53:5

In this last example, the prophet uses repetition to show that not only does undeserved punishment fall on the suffering servant, but the fact of his wounding actually heals us. The second part of the repetition amplifies the first.

Repetition Is Also Structural

But using repetition to emphasize and underscore meanings is only the beginning. The writers of the Bible didn’t stop there. They used repetition to bring structure to their writings, stacking repetition within repetition in chiasms.

A chiasm is a literary pattern that builds meaning by nesting repetitions inside one another. They are all over the Bible, both in poetic and narrative sections. They can be as small as a couplet or as long as a whole book. Chiasms use repetition to highlight the writer’s main idea, make comparisons, and connect the main idea to other subtopics.

Chiasms can have a symmetrical “arrow” structure that can look like this:

A

B

C

D: The center of the chiasm is often a really important idea

C2

B2

A2

Example: One of the Many Chiasms in Genesis 1

Chiams can also have a “staircase” structure like the one below from Genesis 1.

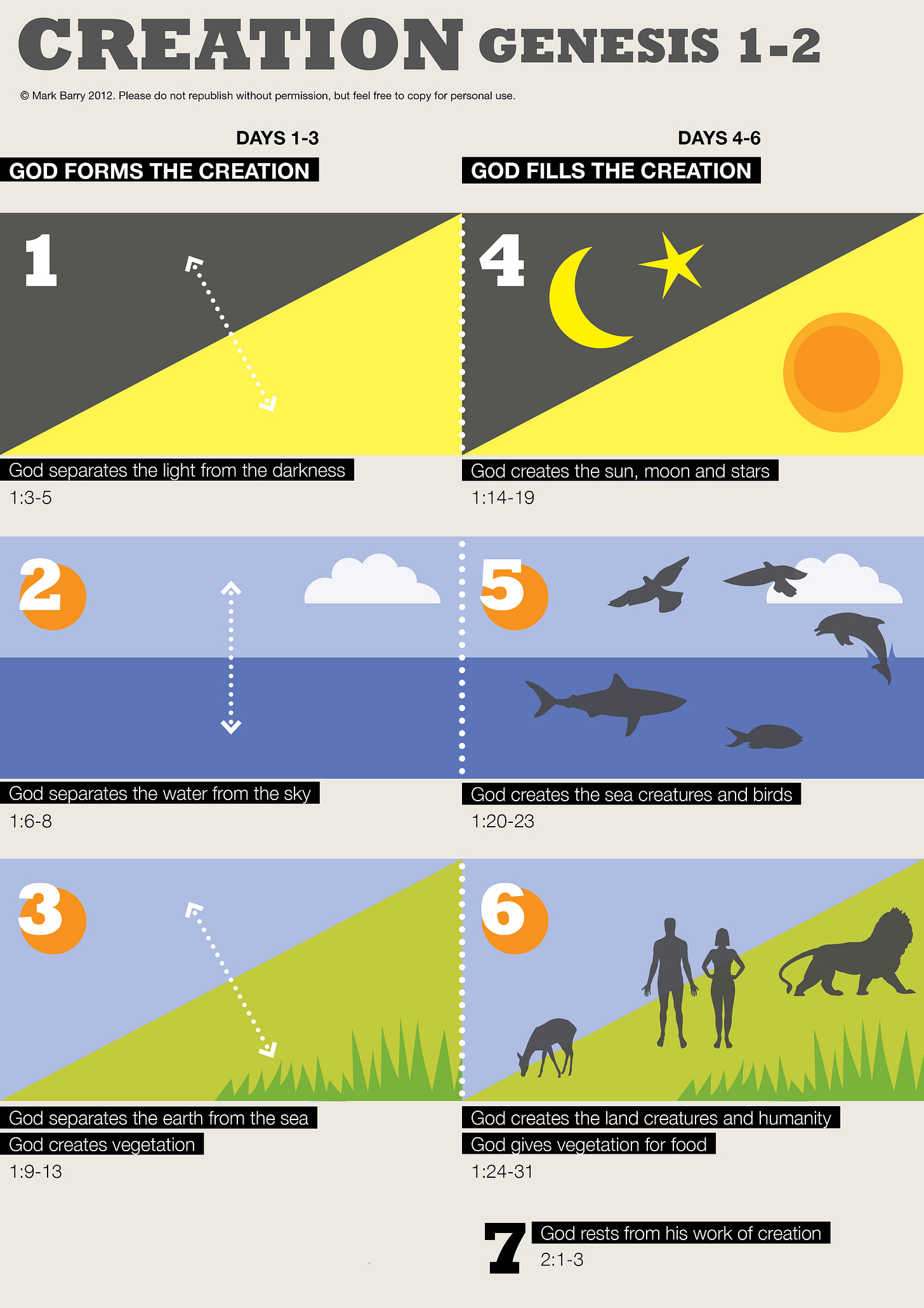

In the first chapter of the Bible, days 1-3 are the days of “forming” and days 4-6 are the days of “filling” but they are repeated chiastically so that the pattern looks like this:

Day 1 —Light and heavens

Day 2—Sky and sea

Day 3—Land

Day 4—Stars and sky for the heavens

Day 5—Birds, fish, and sea monsters for the sky and sea

Day 6—Animals and people for the land

Day 7 The chiasm points to the significance of Sabbath rest.

So it looks like this:

Repetition Can Even Link Passages Together, Deepening the Meaning of Both

Biblical writers used repetitions to enlarge and develop meanings throughout the canon and across the centuries, to echo and allude to previous works, and to prophecy and foreshadow aspects of God’s plan that had not happened yet. This is where we get to the rule “repeated is related.”

Richard Hays’ Theatre Analogy

In order to illustrate the way the Bible references itself, Richard Hays uses the analogy of a theatre in his book, Reading Backwards. Hays writes:

“It is as though the primary action of the Gospel is played out on center stage, in front of the floodlights, while a screen at the back of the stage displayed a kaleidoscopic series of flickering images from Israel’s scripture… If the viewer pays careful attention, there are many moments when the words or gestures of the characters onstage mirror something of the shifting backdrop (or is it the other way around?).

Hays is painting a picture to describe how the Bible treats itself. There is foreground action on the “stage” and the background action that plays out on the screen behind the stage bears a strange resemblance to what is taking place onstage. As you watch you recognize a correspondence between the two. Hays goes on to say:

“Sometimes the correspondence can be discerned only after the second event has occurred and imparted a new pattern of significance to the first.”

So the careful reader of the Bible will read a passage (the action on the stage) and ask themselves the question: does this remind me of any other moments in the Bible (the screen behind the stage)? When you find a repetition, the link between passages forms a channel through which meaning travels both forward and backward. The later passage illuminates the former. The former passage reveals deeper meanings latent in the latter.

Examples of Repetition Between the Old and New Testaments

Let’s work with this theatre analogy a bit by looking at some New Testament moments that have particular Old Testament resonance. After all, you can’t open a page in any of the four gospels without seeing four or five repetitions of Old Testament events, images, characters, or themes.

Transfiguration

In the middle of his ministry, Jesus goes on to the mountain during the transfiguration and the apostles see him glorified and then Moses and Elijah appear. In the context of the theatre analogy, the scene of the transfiguration is happening on stage, while the screen behind them is playing a scene from Mt Sinai when Moses himself went up to the mountain and saw the light and heard God’s voice. Then the screen flashes to a parallel scene when Elijah flees for his life to Mt. Sinai and hears the voice of God and experiences a bit of his glory. The reader should understand that all of these moments in redemptive history are connected.

The River of Life

When Jesus says to the woman at the well that if she asked him for a drink, he would give her a spring of living water coming from inside herself, the river of life that flowed out of Eden would have been playing on the screen behind them. Then it would flash to Ezekiel’s vision of a river flowing out of the temple in Jerusalem. Then, perhaps it would flash to Psalm 1 where the person who meditates on the Torah is likened to the tree of life sinking its roots down into the river of life.

Jesus and Israel

The gospels make the stage-screen connection between Jesus and Israel over and over again. As a child, Jesus escapes to Egypt and returns, just like Israel. In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus gives the new law to his disciples on a mountain, just like Moses and Israel. Jesus is tempted in the wilderness after his baptism, just like Israel. Just as Israel ate the manna in the desert, so Jesus offers a better bread of life. (John 6) Just as Israel drank water from the rock, Jesus offers better living water. (John 2 and 7) The connections go on and on.

The gospel writers take every chance to build the house of meaning for Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection using bricks from the Old Testament. Throughout their works, they take for granted the rule “repeated is related.”

Repetition Within the Testaments

The meaning that comes from the correspondence of events and language in the Bible doesn’t only occur between the testaments, but within them as well. When the writers of books that became the New Testament highlighted repeated things from the Old Testament, they weren’t inventing something new. The Old Testament repeats itself constantly. The writers of the New Testament were just following the pattern of the literature that shaped their culture, their imagination, and their literary expectations.

Examples Inside the Old Testament

Exodus

In their wonderful little book, Echoes of Exodus, Alastair Roberts and Andrew Wilson, show that the “big” exodus out of Egypt was actually preceded by a bunch of smaller exoduses. as several members of Abraham’s family went down to Egypt and returned in the very same pattern.

Tabernacle and Temple

The Tabernacle was the “hot spot” of God’s presence during the years of Israel’s wilderness wandering. The temple was a larger (stationary) version of the same design. However, both of them evoked the primary “temple pattern,” of the Garden of Eden, the first of God’s many “hot spots" in Scripture.

Messiah

The first hint we get of the messiah theme is God’s promise to Adam and Eve that one of their descendants will crush the head of the serpent and destroy the evil it brought into the world. From then on, the Hebrew people carried the hope that an ultimate redeemer would come to deliver them. Across the centuries, messiah-like figures came and went, each bringing micro-deliverance in their own ways. Some were shining moral examples (Joseph, Daniel). Others were not so shining (Samson, Jonah). But all fell short of the promise of the snake-crushing messiah that would one day be fulfilled in Jesus.

Serpents

Speaking of serpents’ heads getting crushed, from Genesis 3 onward, the enemies of God occasionally have a serpentine appearance (evoking humankind’s first enemy). Goliath has armor like serpent scales (then loses his head). The statue of Dagon, a Philistine God that looked snake-like in appearance, fell over when the ark of the covenant was placed beside it (and the head fell off). Even Egypt is called “Rahab” (a sea monster), associating Israel’s physical enemies with Israel’s spiritual enemies.

So What?

The point of all of this is to learn how to be better Bible readers.

If we are going to tune into God’s, life-giving meanings in the Bible, we have to learn how those meanings were communicated through the Bible’s original authors.

That means, among other things, that we have to put down our confidence that we already know what is being said and how it is being said and open the Bible on more humble terms, like travelers in a foreign land where wonders await. Luckily, signposts to those wonders are scattered liberally throughout Scripture and are lit up with the neon glow of repetition.

All we have to do is see and follow.

Photo by Sixteen Miles Out on Unsplash

It's a good insight. Impossible to understand without the helper.